Are We Training Young Athletes the Wrong Way?

Lessons from the Past That Could Change the Future of Youth Sports

We cheer them on from the sidelines. We enroll them in leagues, buy the gear, and celebrate their first big win. For many families, youth sports feel like the perfect path to discipline, fitness, and maybe even a college scholarship. But what if our approach—especially when it comes to early specialization—is actually doing more harm than good?

Across the U.S. and much of the Western world, kids are encouraged to pick a sport early and stick with it. Travel teams, year-round training, private coaching—it all starts younger and younger. The thinking seems clear: the earlier a child specializes, the better their chances of success.

But history—and science—tell a different story.

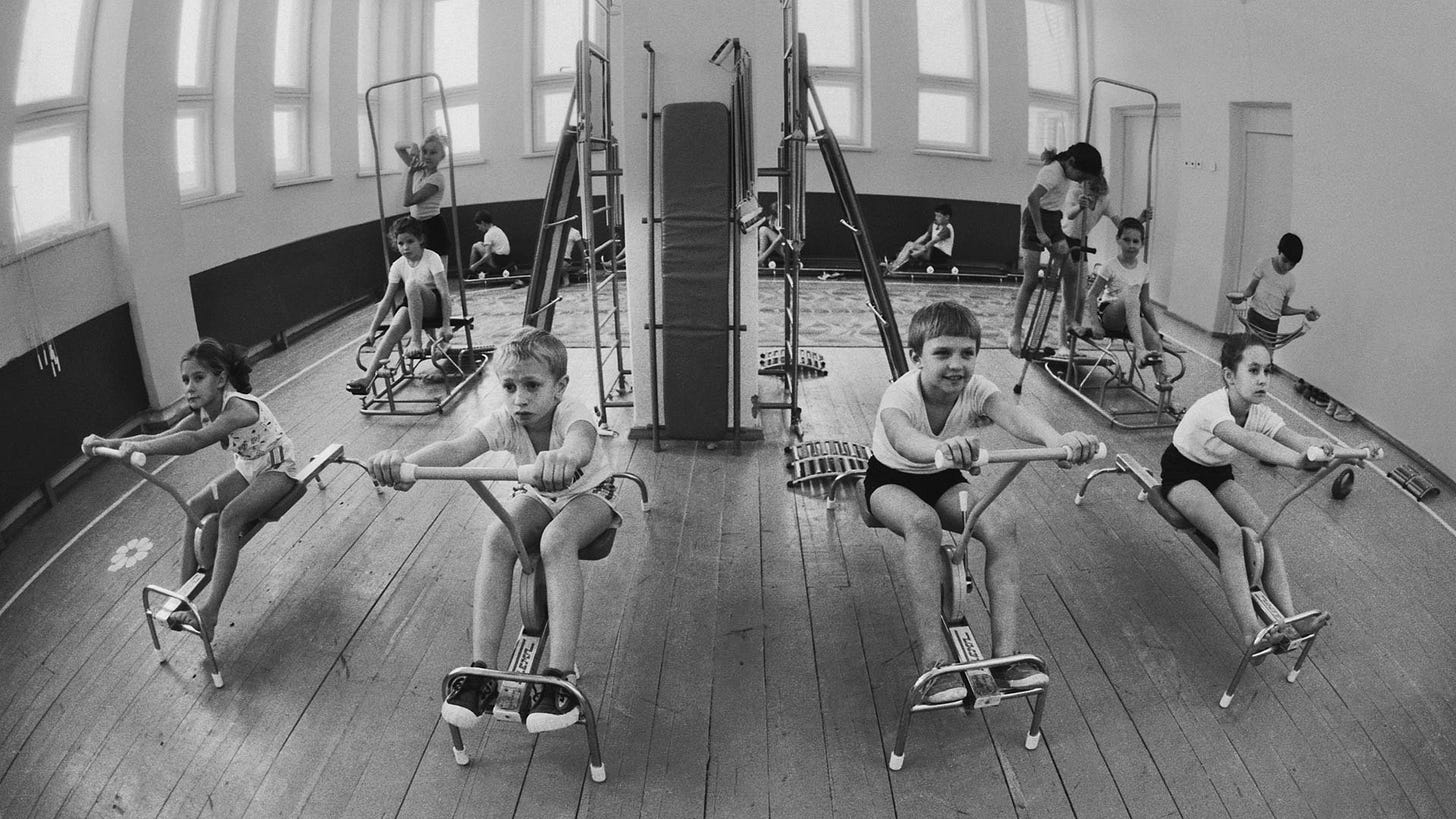

What the Soviets Did Differently

For decades, the Soviet Union churned out elite athletes who dominated international competition. But here’s what may surprise you: they didn’t do it by locking kids into a single sport at age 8. In fact, they took the opposite approach.

Soviet coaches and sports scientists believed in building a broad athletic foundation first. Young athletes didn’t jump straight into intense, sport-specific training. Instead, they ran, climbed, threw, swam, tumbled—you name it. The idea was to create a physically literate athlete first, and a specialist later (Riordan, 1978; Grant, 2005).

Think of it like building a pyramid. A wider base—made up of agility, strength, flexibility, coordination, and endurance—meant a higher potential peak. Only after this base was established did Soviet athletes begin to narrow their focus (Yessis, 1991).

Specialization Came Later—and Worked Better

While Soviet coaches were certainly interested in talent identification, they didn’t rush it. Most athletes didn’t specialize until their early to mid-teens—usually around age 13 to 15 (Bompa & Haff, 2009).

This delayed specialization came with some key benefits:

It gave kids time to explore a range of physical activities.

It reduced the risk of overuse injuries (DiFiori et al., 2014).

It helped athletes stay mentally engaged and avoid burnout.

It developed more adaptable, well-rounded athletic abilities (Yessis, 1991).

Once athletes were ready to specialize, they were stronger, more skilled, and less prone to the imbalances and injuries that plague many young competitors today.

The Western Model: Sport as the Only Path to Fitness

In contrast, many Western systems—especially in the U.S.—often treat organized sport as the main (or only) form of physical development for children. If a kid likes soccer, we put them in year-round leagues. If they show talent in baseball, we sign them up for a travel team and private lessons by age 10.

That might lead to early success, but it comes at a cost.

Kids who specialize too early are more likely to:

Develop overuse injuries (Jayanthi et al., 2013)

Burn out or quit sports altogether (DiFiori et al., 2014)

Miss out on foundational movement skills

Become athletes who are good at one thing—but not well-rounded movers

Take a soccer player, for example. They may have great lower-body endurance and coordination but never develop upper-body strength or the body awareness that comes from climbing, swimming, or gymnastics.

And when sport is treated as the only path to fitness, kids who drop out of competition often stop moving entirely.

We’ve Been Here Before: The Turner Halls

Believe it or not, the U.S. once had its own version of this broad-based approach to physical development—long before Soviet dominance on the world stage.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, German-American “Turner” societies established Turner Halls across the country. These weren’t just gyms; they were community spaces built around holistic movement and physical education for all ages.

Turners emphasized gymnastics, calisthenics, and general physical training. Their goal? Not just athletes—but well-rounded, physically capable individuals (Hackensmith, 1966). Over time, though, this model faded as schools and communities began prioritizing competitive team sports. The Turner vision of lifelong movement got lost in the shuffle (Rader, 1999).

Two Philosophies, One Big Difference

So what’s the big takeaway here? It’s not just about training style—it’s about mindset.

The Soviet model (and earlier American models like the Turners) saw childhood as the time to build overall physical competence. Sports came later.

The modern Western model often uses sports as physical development, even when it’s narrow, repetitive, and high-pressure from a young age.

When kids spend their entire childhood focusing on one sport, they often develop limited movement patterns. A swimmer might be lightning-fast in the pool but lack agility on dry land. A baseball pitcher could throw heat but struggle with mobility or injury from muscle imbalances (Bompa & Haff, 2009).

So... What Should We Be Doing Instead?

This isn’t about banning youth sports or criticizing competitive programs. Youth sports offer real benefits—teamwork, goal-setting, self-confidence. But we need to expand how we think about movement and athletic development.

Here’s what a better approach might look like:

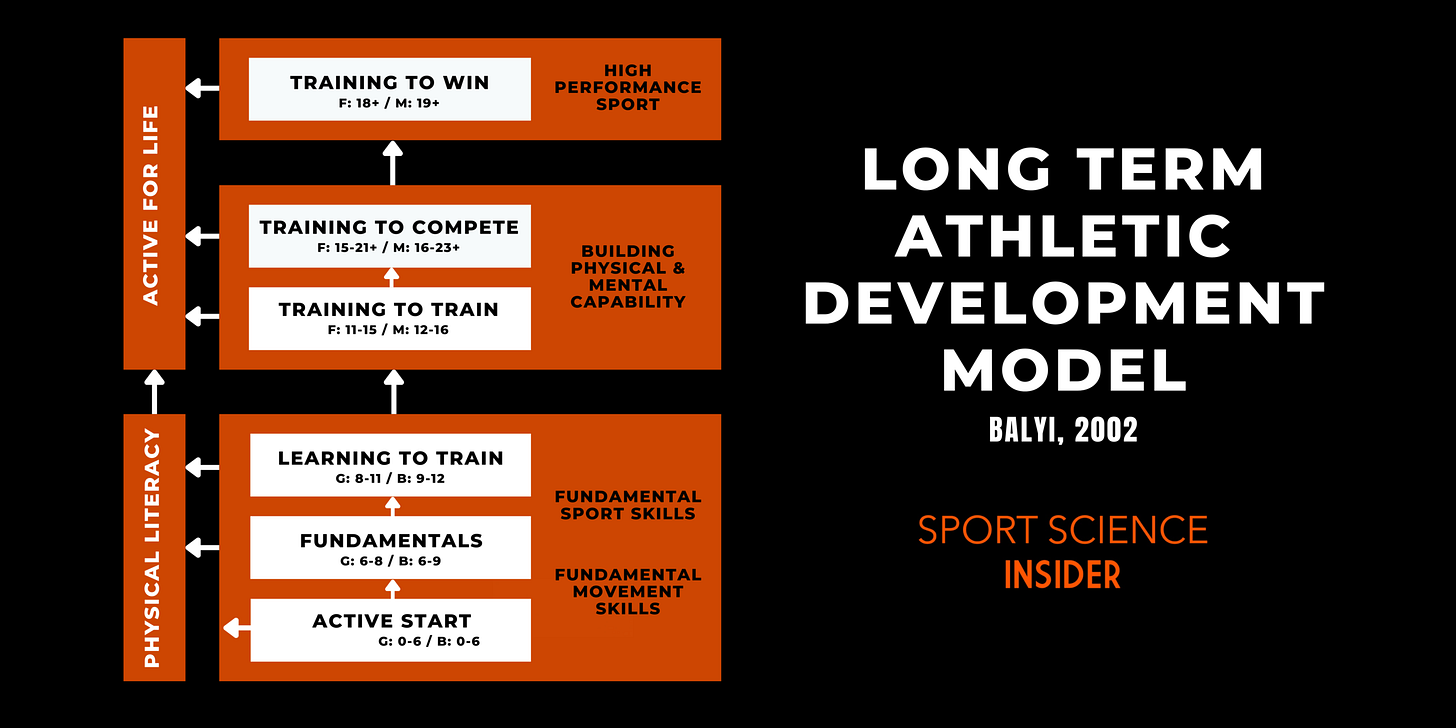

Encourage multi-sport participation until at least age 13 or 14 or later

Incorporate general movement skills into training and physical education: sprinting, climbing, tumbling, swimming, throwing, etc.

Prioritize movement quality over game-day wins in early years

Teach coaches and parents to value long-term development over short-term results

Promote physical literacy as the foundation for all sports—and lifelong health

Final Thought: Think in Pyramids, Not Pipelines

If our goal is to develop better athletes—and healthier kids—we need to stop thinking of youth sports as a pipeline to the pros and start treating them as a place to build strong, capable bodies that can move well in any context.

Early specialization might create early success—but it doesn’t necessarily create better athletes. Let’s start building the base first.

Until next time,

References

Bompa, T. O., & Haff, G. G. (2009). Periodization: Theory and methodology of training (5th ed.). Human Kinetics.

DiFiori, J. P., Benjamin, H. J., Brenner, J. S., Gregory, A., Jayanthi, N. A., Landry, G. L., & Luke, A. (2014). Overuse injuries and burnout in youth sports: A position statement from the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 48(4), 287–291.

Grant, G. (2005). Soviet sport in the making of the new man. Manchester University Press.

Hackensmith, C. W. (1966). History of physical education. Harper & Row.

Jayanthi, N. A., Pinkham, C., Dugas, J., Patrick, B., & LaBella, C. R. (2013). Sports specialization in young athletes: Evidence-based recommendations. Sports Health: A Multidisciplinary Approach, 5(1), 7–11.

Rader, B. G. (1999). American sports: From the age of folk games to the age of televised sports (4th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Riordan, J. (1978). Sport in Soviet society: Development of sport and physical culture in the USSR. Cambridge University Press.

Yessis, M. (1991). Soviet training and fitness methods. Yessis Press.

Thank you. Youth sports have gotten out of control. Let the kids play.